Peer Sam

Open Arms Peers express their feelings on the situation in Afghanistan

In the conversation about the impact of the Taliban returning to government in Afghanistan, I guess there’s a sense of trying to make meaning of what our time spent there meant. It’s hard for me to express sometimes, because my experience doesn’t include deployments to Afghanistan, or anywhere else, but Afghanistan is where my life changed, despite not having been.

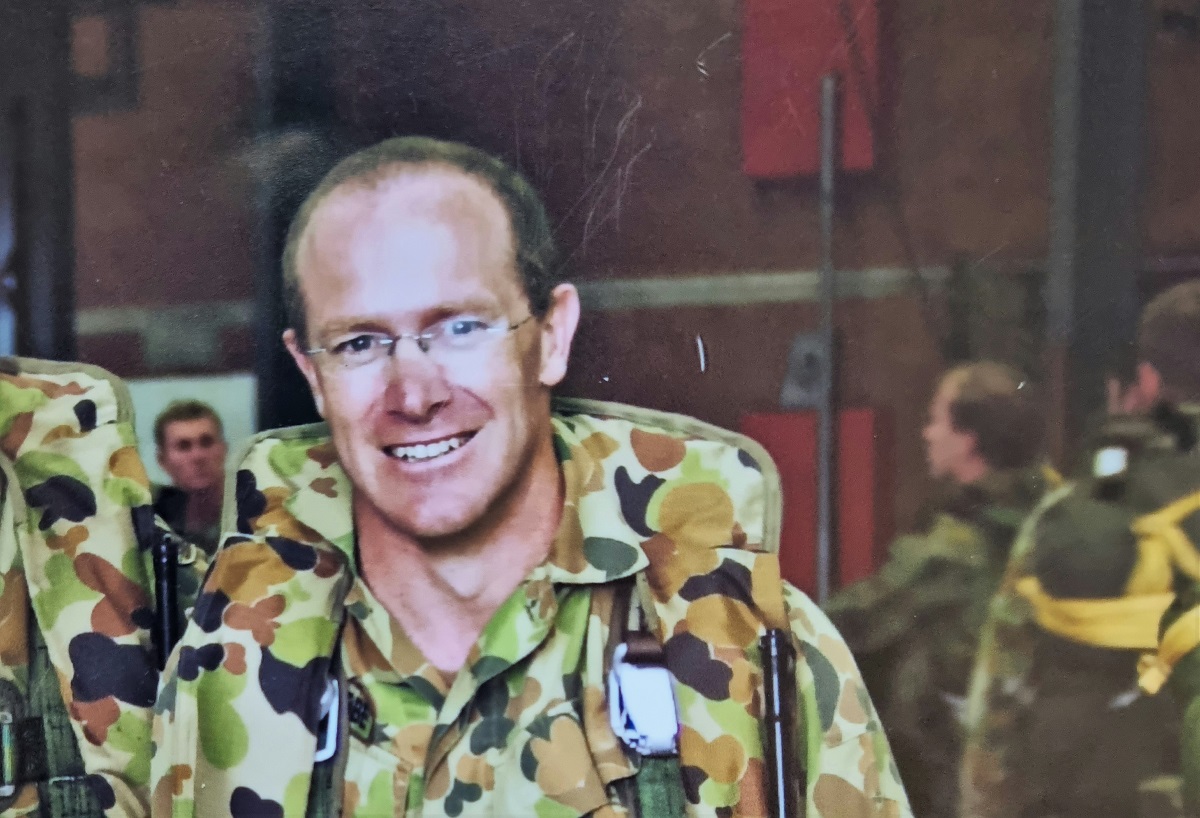

My dad (pictured) deployed to Afghanistan in 2010. I joined the Army in early 2011 while he was away. He went over as an energetic, excited and committed person and officer and returned with a grey, deadened demeanour.

His time in Afghanistan changed him in ways that I didn’t understand at the time but do now.

The way he changed impacted his relationships with all of my family, and while he was trying to find his way home, and before he and I were able to discuss what happened during his deployment that affected him so much, he died.

The grief of losing my dad without the understanding of what had happened around him or to him that made him change is extraordinary. Especially considering that I was, by the time he died, a soldier in my own right and at the start of my military career, so I was not totally blind to the context in which he had been injured.

The way that the conflict in Afghanistan has finished has asked me to make meaning (again) of the loss of a parent, the sacrifice we made as a family, the sacrifices he made as a parent, a husband and more unknowingly the sacrifices to his mental and physical health, to ask again whether it was worth it, what was achieved and do I deem it worthwhile.

The answers to those questions are in layers and shades of grey.

Some yes and some no, some without a definite answer. The judgements, meanings and symbols are all my own – they don’t (and can’t) generalise to the majority.

I think it’s incumbent on all of us to seek to make our own meaning out of whatever Afghanistan symbolises to each of us. The media can’t give us a satisfactory answer, nor can the politicians or historians.

I think there has to be a comfort in “my truth”.

An understanding that “my truth” doesn’t equate to anyone else’s or objective fact, but a comfort in knowing our intention, what we achieved personally and where we made meaningful contributions.

Giving ourselves permission to feel and experience the full spectrum of emotion is an important part of making that meaning, and so is connection with others that share the same or similar experience. Connecting with people with the intention of finding words around our inner experience is how the healing starts and continues.

Counter to that, there is no obligation to have a feeling about anything, you are allowed to be indifferent, settled and comfortable.

Peer Sam

If you, or someone you know in the veteran community or a military family, need to talk, we’re here 24/7 to listen. 1800 011 046